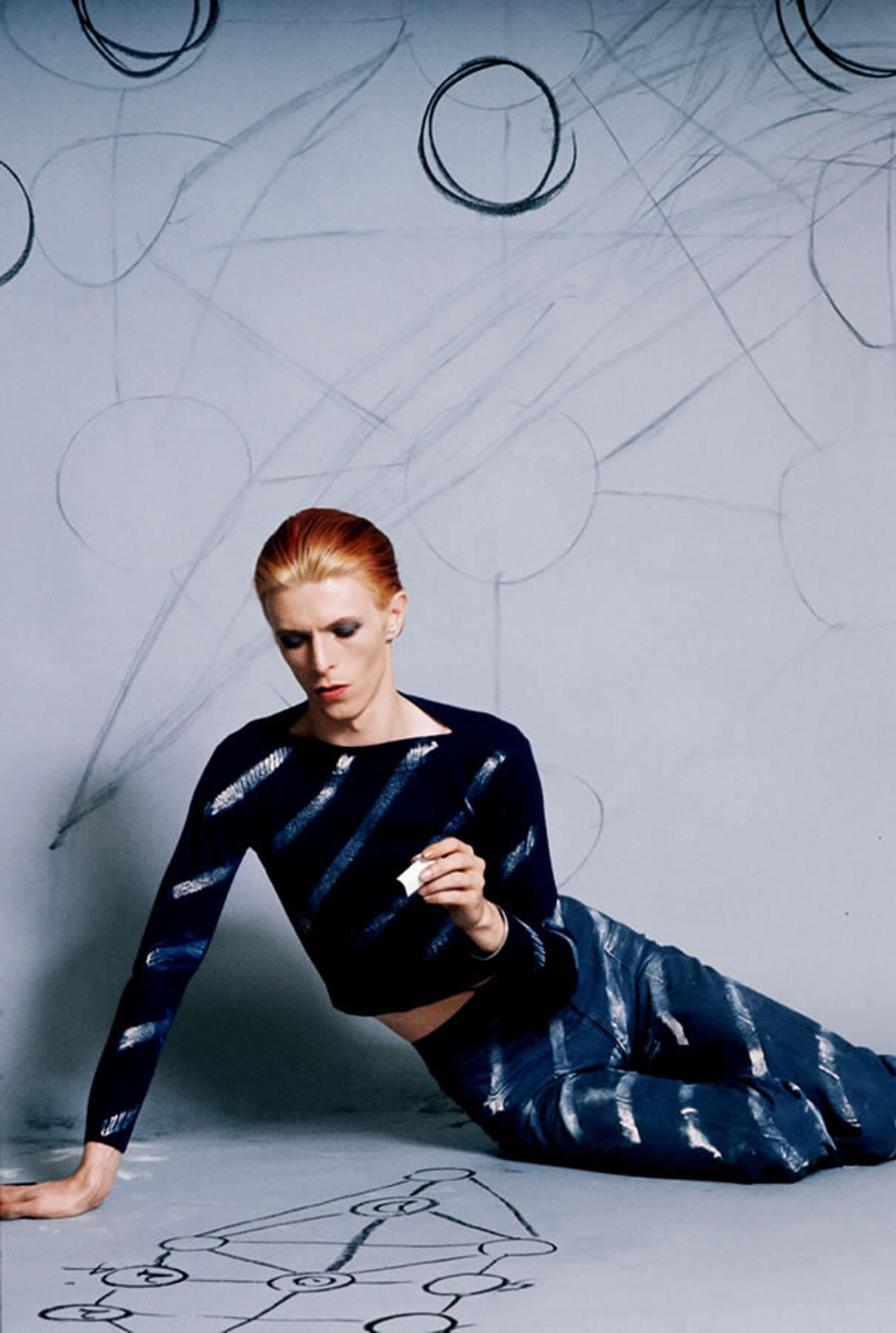

Photo by Steve Schapiro of Bowie

drawing the kabbalistic tree of life

David Bowie and the 20th Century Occult Revival

Rob Howells

Article for Kindred Spirit Magazine, published 2017

To mark the one-year anniversary of the death of David Bowie Robert Howells reflects on the creative icon’s place in the wider occult revival of the late 20th Century.

“I’m closer to the Golden Dawn, immersed in Crowley’s uniform of imagery.” Quicksand, David Bowie 1971

Just prior to his death a year ago David Bowie released a video for his song Blackstar that was imbued with occult references. The video takes place on a distant plane beneath a black sun where a figure finds the corpse of an astronaut. The skull of the astronaut is taken to be worshipped during a ritual among scenes of crucifixion and Bowie himself appearing variously as a preacher and a trickster figure.

Watch the Blackstar video on YouTube

The Blackstar video revisits a number of Bowie’s occult interests and marks a farewell to Bowie’s enduring character of Major Tom whose astronaut, an explorer of inner and outer space, mirrors Bowie’s own journey. The black sun is a traditional symbol of inner wisdom that draws on the occult and can be found in the writings of alchemists and the art of Jean Cocteau. A second reference to the source of occult knowledge is shown in the ritual worship of a human skull which harkens back to the Templar veneration of the skull named ‘Baphomet’ and the medieval grimoires of the Picatrix and Agrippa’s books on occult philosophy. Bowie also appears dressed in a striped outfit that directly references an earlier point in his career when he studied the occult applications of the kabbalah.

In 1971 he released the album Hunky Dory which drew upon the many influences and interests of Bowie at the time and included the song Quicksand which referenced Aleister Crowley and The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. The Golden Dawn began in the 19th century as a research group into the occult by drawing upon Freemasonry and others sources to build a system of rituals aimed at developing the individual. Crowley was initiated into order but eventually left to form his own group. Although loathed by the establishment and branded wicked and depraved by the press Crowley was a revolutionary thinker and rigorously examined all forms of spiritual practice, partly to satisfy his own cravings but also to explore the limits of religion.

Although he references Crowley on more than one occasion Bowie himself seemed sceptical of the convoluted nature of his writings preferring instead the works of other members of the Golden Dawn magickal society, Israel Regardie, MacGregor Mathers, Dion Fortune and Arthur Edward Waite. Regardie provided a less convoluted interpretation of some of Crowley’s works, Mathers was a pioneer of 20th century magick, Waite a Rosicrucian historianand Fortune had authored the classic Psychic Self–Defence. Manly P. Hall was also key in Bowie’s occult research and his unsensational The Secret Teachings of All Ages magnum opus continues to be a reputable source of information on matters of the occult.

In his youth Bowie sought a true form of spirituality with his explorations into the occult which he shared with his audience but he was not alone in bringing the occult to the masses through music. He had come of age in the 1960s atmosphere of spiritual exploration and a renewed interest in alternative beliefs. Before him the Rolling Stones had dabbled in updating the blues tradition of referencing the dark arts with Their Satanic Majesties Request album and Sympathy for the Devil song. Their referencing of Satan was a first in popular music and the Stones used this to emphasise their ‘bad boy’ image. In spite of their occult references they never practiced magick and when occult film maker Kenneth Anger offered the band roles in his art film Lucifer Rising they withdrew from the idea. Sympathy for the Devil portrayed Jagger as Lucifer himself but it was an act. Like Bowie, Jagger was adept at using personas to narrate songs and Jagger’s entire public persona belied his intellectual prowess to fit into a band aimed at appealing to working class youths.

The Stones were originally positioned as the antithesis of the clean-cut and well behaved Beatles, but these also saw fit to include Crowley as a ‘person of interest’ on Peter Blake’s cover for Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. As exponents of the psychedelic experience The Beatles would inspire many to flock to India to escape consumerism and embrace the many forms of yoga and meditation. This in turn led to a greater interest in spiritual teachers from both the East and West and many seekers would discover the methods of Buddhism, Taoism and Sufism for the first time. While NASA was putting astronauts on the moon, the ‘internauts’ made their own psychedelic journeys into the uncharted realms of the mind using LSD. Bowie related the moon landings and Kubrick’s evolution of humanity onto his own sense of alienation in the song Space Oddity.

As the occult was finding a voice among the youth movement it was also becoming devalued through the medium of music. Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin was a serious practitioner of the occult and bought Crowley’s house in Scotland while the band adopted occult symbolism for their album covers and concerts. They laid the groundwork for the occult as a staple element of hard rock but it was Black Sabbath, who littered their work with occult references, who appealed to the (black) masses and spawned an industry of heavy metal occultists. Alice Cooper and others followed from glam rock to the gothic crypt of rock music but their approach trivialised the sacred and was more in keeping with Hammer Studios horror films than any serious exploration of occult arts. The allure of the occult for many is the idea that will bestow on upon the practitioner power over others but like any authentic spiritual practice it can only really offer dominion over the self.

Bowie remained aloof from the exploitation and his preoccupation with the occult remained for him an intellectual pursuit to satisfy his own personal development. The song Quicksand also explores human potential with the line “I’m just a mortal with potential of a superman”. On Oh! You Pretty Things from the same album he sings “Make way for the Homo-Superior” revealing how taken he was with by the idea of Nietzsche’s coming superman. The same conclusion had been reached by Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s Rosicrucian inspired novel Vril: The Power of the Coming Race in the late 18th century. These ideas had in turn inspired and underpinned the Thule and Vril societies in Germany during the early 20th century that led to the occult foundation of Nazi ideologies and symbolism.

BOWIE – QUICKSAND (DEMO VERSION) 1971 from Gia on Vimeo.

“I’m living in a silent film, portraying Himmler’s sacred ream of dream-reality.”

Quicksand, David Bowie 1971

The Nazis had adopted occult trappings to rival the power Christianity still held over the masses and while they owed a debt to misinterpretations of Nietzsche and Theosophy it was Heinrich Himmler who believed in creating supermen. Himmler’s pursuit of the occult was typical of weak-minded personalities who believe it will give them power they would not otherwise deserve but these ideas continued to fascinate Bowie and appeared again in 1976 when he had adopted his Thin White Duke personae for Station to Station. The title track from the album was structured around the occult version of the Kabbalah. The occult Kabbalah is an important tool in the Western occult tradition and draws on the orthodox version from Judaism but is not related to the new age incarnation later adopted by Madonna and her film star friends. The Kabbalah was central to the writings of Aleister Crowley whose White Stains book of obscene poetry Bowie uses as a pun in the song.

“Here are we, one magickal movement from Kether to Malkuth.”

Station to Station, David Bowie

Kether and Malkuth are the highest and lowest spheres of existence on the Kabbalistic Tree of Life, a design of ten ‘sephirot’ with connecting paths that represent different magical workings from the material plane of Malkuth ascending to the enlightened realm of Kether. Bowie’s description of a single ‘magickal movement from Kether to Malkuth’ is reversed in that it goes from the divine to incarnate in the material sphere. Bowie returned to his Kabbalistic leanings in the Blackstar video shortly before his death. In one scene he wears an outfit painted in white diagonal stripes. He had worn the same outfit for the 1976 Station to Station photo shoots in which he is pictured with his drawings of the Kabbalistic tree of life.

As with the song Quicksand at the time of recording Station to Station Bowie was faced with his own potential mortality and mental collapse. He had become overwhelmed by his lifestyle in America and Station to Station shows him searching for love and connection while fighting of severe drug dependency to a glacial electronic score. He spoke at the time of falling prey to psychic vampires and of being targeted by witches while steeped in the paranoia of his immense cocaine habit. At constant risk of overdosing Bowie had also likened the journey in Station to Station to that of the Stations of the Cross, a ritual that follows the fourteen final points that Jesus experienced on the road to Golgotha. The album also contains the song Word on a Wing in which prayers are spoken to request acceptance into God’s scheme only to conclude that he was ready to shape that scheme although he took to wearing a crucifix at this time.

Christianity remained an inescapable part of his Bowie’s background and his relationship with it was unsurprisingly complex. In an early song Holy, Holy, a single b-side from 1970, Bowie had rejected religion outright but he revisited Christianity in many provocative forms throughout his career including appearing in 'The Next Day' video dressed as Jesus, the Blackstar video depicting three writhing crucified figures or his awkward recital of the Lord’s Prayer to mark the death of Freddie Mercury. Ziggy Stardust, his most religiously potent creation, was the messianic figure of an alien rock star who was sacrificed by his fans. Ziggy’s rise was interchangeable with Bowie’s ascent to stardom and he abruptly laid the character to rest in 1973 to free his own personality which had become overtly identified with his creation.

Ziggy was only one the many identities that Bowie would adopt and discard during his career and through his myriad of personalities Bowie had been at times Buddhist, Christian, Kabbalistic, messianic, apocalyptic and an occultist. For his 2002 album he settled on the title Heathen, which in the guise of learned pagan made perfect sense. Bowie had a shrewd intellect that is rare in occultism and rarer still in the music industry. He would draw on facets of his own personality, from his ideas and style to his sexuality, and challenge culture to expand to include the widest possible view of humanity. It was a continuation of Renaissance view of studying everything from all sides and refusing to specialise. This enabled him to draw on ideas that span the human condition and to embody an ongoing experiment of uniqueness.

His final year was spent in part working on a stage play aptly named Lazarus which matches the Buddhist sentiment of death a reincarnation. For the end of his life he chose to return to Buddhism by requesting cremation and the scattering of his ashes at a Buddhist ceremony in Bali, Indonesia. He had come full circle not just in terms of the cycles of nature but in his own spiritual journey and as the music press opines that we’ll not see his like again the fans can take comfort in his final works and reply that perhaps we will.

“Child of Tibet, you’re a gift from the sun, reincarnation of one better man.”

Silly Boy Blue, David Bowie 1967

Robert Howells is the author of The Illuminati: The Counterculture Revolution from Secret Societies to Anonymous and WikiLeaks.

ISBN: 9781780288727

Watkins Publishing Ltd - October 2016